Plurality ⿻

Chapter 6, part 2 of Technological Metamodernism

Previously:

Reader: So we ended last chapter with you saying d/acc needs more on the “democratic” side. You mentioned Audrey Tang and something called “Plurality.” I’ve heard the name—Taiwan’s tech minister who did something interesting with digital democracy? But honestly, when I think of government and technology together, I usually think of surveillance states or opaque websites that haven’t been updated since 2003.

Hilma: That’s precisely the reflex we need to overcome. And Tang’s work provides promising evidence that digital government can be genuinely different—not surveillance apparatus or bureaucratic nightmare, but infrastructure for collective intelligence and democratic renewal.

Plurality (數位 or just ⿻ )–developed by Tang and economist Glen Weyl–is even broader than d/acc in its scope. It’s really a whole worldview, and has the hope of inspiring a transnational political movement.

In their book, Tang and Weyl define it most succinctly as “technology for collaboration across social difference”. And here’s how Tang put it in her 2016 job description as Digital Minister, which I find more evocative:

When we see “internet of things,”

let’s make it an internet of beings.

When we see “virtual reality,”

let’s make it a shared reality.

When we see “machine learning,”

let’s make it collaborative learning.

When we see “user experience,”

let’s make it about human experience.

When we hear “the singularity is near” —

let us remember: The Plurality is here.

Notice her metamodern rhetoric—taking the dominant tech industry framings and insisting on human and collective alternatives. Not rejecting the technologies, but redirecting them toward fundamentally different ends.

Reader: Okay, you’ve got my attention. But before we dive into the philosophy, I’m curious to hear more about this Audrey Tang. How does someone end up implementing experimental digital democracy at national scale?

Hilma: Tang’s trajectory is genuinely extraordinary. Born in Taipei in 1981, she left formal schooling at fourteen, finding it too slow. She taught herself advanced mathematics, classical literature, and multiple programming languages. At nineteen, she founded her first software company in Silicon Valley. By her mid-twenties, she was a leading figure in the global open-source community—contributing to Perl, helping develop internet standards, building bridges between programming languages and the communities behind them.

What’s remarkable isn’t just the technical brilliance but how Tang approached technology as fundamentally social. She wasn’t interested in code for its own sake, but in how software could enable human collaboration across differences. This has become the through-line of her career.

Reader: So she’s this brilliant programmer-philosopher. How does that translate into government work?

Hilma: The bridge was the g0v community she helped build, and then the Sunflower Movement that brought it to national attention.

g0v—pronounced “gov-zero,” with the “o” replaced by a “0”—took a distinctive approach to civic tech: they would “fork” government websites, building shadow versions that were more transparent, usable, or functional. Their famous early project took Taiwan’s dense national budget and rebuilt it as an interactive visualization citizens could actually explore. The philosophy was (a very metamodern) ‘constructive criticism through building’—don’t just complain that government services are bad, demonstrate what they could look like, creating both public pressure and ready-made templates for improvement.

This methodology proved its worth during the Sunflower Movement in 2014. Taiwan’s legislature was rushing through a trade agreement with China that many saw as threatening democracy and sovereignty. Students occupied the parliament for three weeks, and g0v provided infrastructure that transformed the occupation into distributed democratic deliberation at scale.

The occupation succeeded partly because it demonstrated viable alternatives—the activists deliberated more effectively than the legislators had. The government noticed. By 2016, Tang became Taiwan’s Digital Minister, a position created specifically for her approach.

Reader: And I believe she recently won the Right Livelihood Award?

Hilma: Yes, Tang won the 2025 award—often called the “Alternative Nobel Prize”—for “advancing the social use of digital technology to empower citizens, renew democracy and heal divides.”

Since leaving the ministerial role in 2024, Tang has become Taiwan’s Cyber Ambassador and a Fellow at Oxford’s Institute for Ethics in AI. More importantly, she’s actively exporting Taiwan’s model—working with California, Japan, and numerous jurisdictions seeking alternatives to surveillance capitalism and authoritarian control.

What makes Tang’s work significant for our purposes is that she’s not theorizing from the academy—she’s proven these systems work at national scale, under intense pressure, in a geopolitical environment where Taiwan faces more disinformation attacks than anywhere on Earth. As she puts it: “Other places have to pay for penetration testing. In Taiwan, we get it for free—two million cyber attacks every day.”

Reader: Tell me more about the actual tools Tang and colleagues developed.

Hilma: vTaiwan is perhaps the most documented example of Plurality principles in action. The g0v community developed it in 2015, directly inspired by the Sunflower Movement’s success at finding common ground during crisis. The platform was designed not to replace traditional democratic processes but to complement them—surfacing consensus on contentious policy issues before they reached formal legislative channels where partisan dynamics would harden positions.

Let me walk you through how it actually worked, using the Uber case as illustration—it’s both the most well-known example and reveals the process clearly. The controversy was the same as everywhere: Uber arrived claiming to be a technology platform, not a taxi service, and thus exempt from taxi regulations. Traditional taxi drivers were understandably furious—they’d paid for expensive medallions, submitted to regulations, paid taxes. Uber drivers were undercutting them while avoiding those costs.

But it wasn’t just taxi drivers versus Uber. You had passengers who loved the convenience and lower prices. Rural communities saw potential for better transportation access. Labor advocates worried about gig economy exploitation. Safety regulators had concerns about oversight. Each group had legitimate interests and valid concerns.

In most jurisdictions, this played out as street protests, political battles, court cases—messy conflicts that eventually got resolved through some combination of political power and legal rulings. In Taiwan, they tried something different.

Reader: Let me guess—they used vTaiwan?

Hilma: Exactly. The Ministry of Transport opened a vTaiwan consultation on how to regulate ride-sharing in late 2015. The process involved multiple stages: proposal, opinion collection, deliberation, and synthesis.

But the crucial innovation was using a tool called Pol.is for the opinion collection phase. Pol.is works like X/Twitter or any microblogging platform—users can submit short statements responding to a prompt. For example: “What responsibilities, if any, should platforms have for the ride-sharing services facilitated through their apps?”

Where Pol.is differs radically from X/Twitter is that instead of replying to or retweeting others’ statements, you simply vote them up or down. No replies means no room for trolls to hijack conversations, no dunking for points, no escalating outrage cycles.

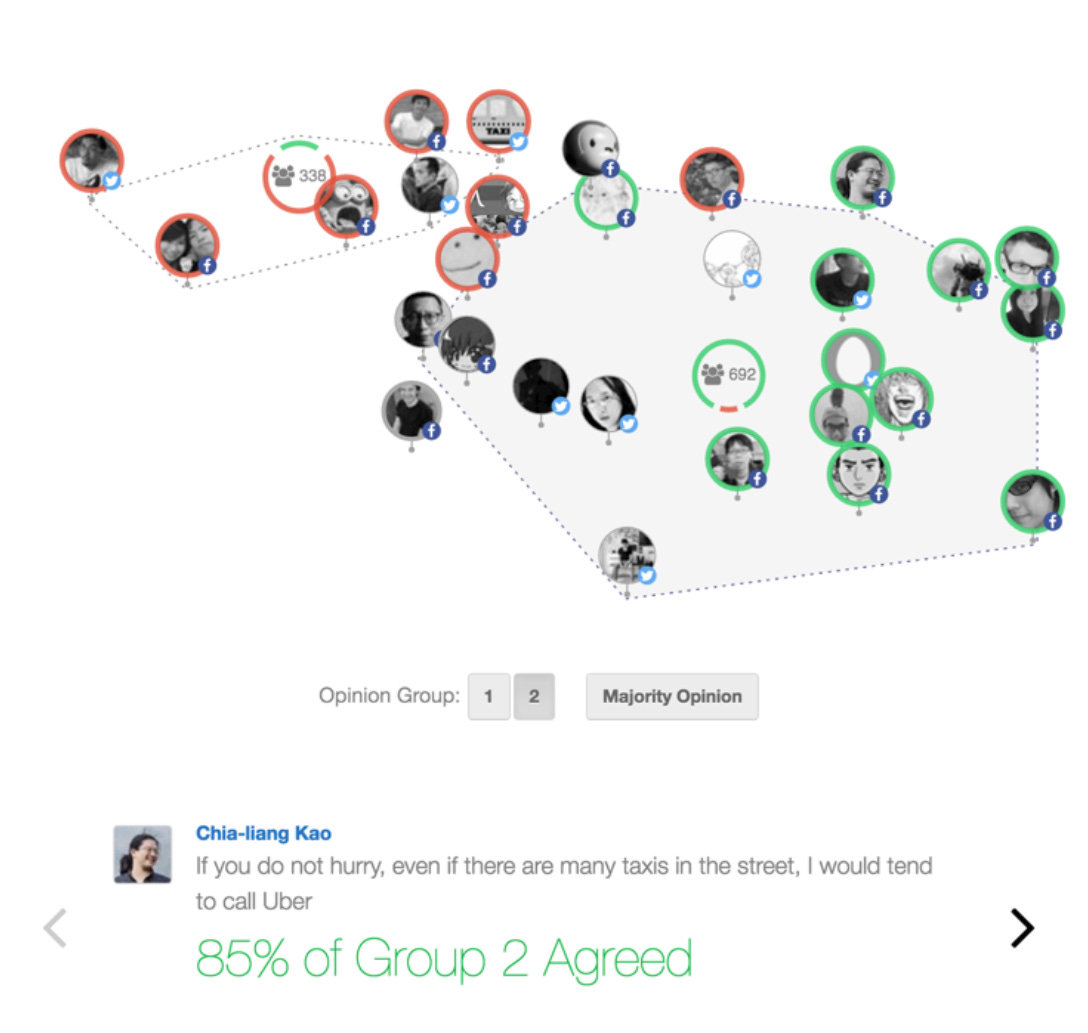

As you vote, something fascinating happens. The system uses machine learning—specifically dimension reduction techniques—to cluster participants based on voting patterns. You see your avatar moving toward a group of people who vote similarly to you. The visualization shows you the landscape of opinion: how many distinct perspectives exist, how far apart they are, where the divisions lie.

But—and this is crucial—Pol.is doesn’t just show you your tribe. It highlights statements that bridge divisions: proposals that receive support across clusters that usually disagree. These bridging statements rise to prominence, creating competitive dynamics where people try to craft ideas that appeal beyond their own group.

Reader: So instead of algorithms that maximize engagement through enragement, you get algorithms that maximize bridge-building?

Hilma: Precisely. The system creates fundamentally different incentives. On X/Twitter, often people get visibility by saying something that triggers their opponents—the algorithm rewards polarization. On Pol.is, you get visibility by finding common ground.

After three weeks of the Uber consultation, something remarkable emerged: Pol.is showed that despite participants initially appearing divided, they actually agreed on many important principles. A synthesis was presented to the Ministry of Transport, which incorporated it into draft regulations. These passed into law, creating what’s essentially a regulated ride-sharing framework that most parties could live with—not love, necessarily, but accept as legitimate because they’d participated in crafting it.

Reader: One successful consultation is nice, but does this actually scale? How many issues did vTaiwan address?

Hilma: From 2015 to 2019, vTaiwan held detailed deliberations on twenty-eight issues. About 200,000 people participated over that period—roughly 1% of Taiwan’s population. Importantly, 80% of the consultations led to actual legislative action.

The topics ranged widely: financial technology sandboxes allowing experimental fintech services, responses to non-consensual intimate images, regulation of online alcohol sales, company registration procedures, and eventually AI governance. Most focused on questions around technology regulation—areas where rapid change creates genuine uncertainty about appropriate rules.

Reader: You said “from 2015 to 2019.” What happened after? Did it collapse?

Hilma: vTaiwan faced real challenges. The platform was deliberately high-touch and intensive—it required significant volunteer effort to facilitate consultations, synthesize inputs, and coordinate with government agencies. When COVID hit in 2020, the loss of in-person meetings significantly disrupted the community’s rhythm. Participation declined.

There was also a structural limitation: the government didn’t have to respond to vTaiwan consultations. When agencies were committed and engaged, the process worked beautifully. But without mandatory response requirements, consultations sometimes disappeared into bureaucratic silence, frustrating participants.

Happily, the experience inspired something more durable: the government’s official Join platform. Join has a lighter-weight interface and broader scope—it addresses everything from school start times to environmental regulations.

The crucial feature: if a proposal on Join receives 5,000 signatures, the relevant government ministry must respond. This enforcement mechanism ensures participation leads to actual engagement rather than performative consultation.

Join has extraordinary reach—roughly half of Taiwan’s population has used it over its lifetime, with an average of 11,000 unique daily visitors. This is democratic infrastructure operating at genuine scale, not pilot projects that work only in controlled conditions.

Reader: This feels very specific to Taiwan’s context—small country, tech-savvy population, unique geopolitical pressures. How does this translate elsewhere?

Hilma: This is precisely what makes recent developments so significant. California launched “Engaged California” in early 2025, initially planning to address youth social media use. But when wildfires devastated Los Angeles, they pivoted immediately to using Pol.is for wildfire recovery and prevention consultations. Japan’s Team Mirai party used similar tools, and Takahiro Anno won a seat in parliament with a platform crowdsourced through Pol.is. Finland ran a consultation on the use of AI in public services using these methods in September 2025.

Each context adapts the tools to local needs and cultures. But the underlying principles travel: create spaces for finding common ground, use algorithms that reward bridge-building rather than polarization, close the loop between participation and actual decision-making.

The fact that it’s working in contexts as different as California, Japan, and Finland suggests the approach isn’t actually Taiwan-specific. What Taiwan provided was proof of concept at national scale. Now others are adapting and extending it.

Reader: Alright, I’ve got the basic idea—digital tools for democratic coordination. But you said Plurality is “really a whole worldview.” That seems like a big claim for some consultation software.

Hilma: You’re right to push back. Let me unpack what makes Plurality more than just clever civic tech.

The term “Plurality” itself is doing significant conceptual work. In Mandarin, the characters 數位 (shuwei)—mean simultaneously “digital” and “plural” when applied to different contexts. This linguistic fusion captures something essential: digital technology and plural social organization aren’t separate domains to be connected but fundamentally intertwined possibilities.

The philosophical foundation weaves together three traditions. Hannah Arendt’s concept of plurality as the fundamental human condition: we exist not as isolated individuals or undifferentiated mass, but as unique persons defined by intersecting relationships and affiliations. Danielle Allen’s vision of a “connected society” where bridging ties across difference form at high rates—diversity becomes valuable only when combined with connection. And Tang’s own design principle: digital technology should build engines that harness social diversity while containing its conflicts, just as industrial technology built engines that harnessed fuel while containing explosions.

These map onto three domains: descriptive (Arendt)—this is how the social world works; normative (Allen)—this is what we should value; prescriptive (Tang)—this is how technology should be designed.

But Plurality extends further. Weyl and Tang argue this framework applies to all complex phenomena—cities, ecosystems, economies, even weather systems. Complexity emerges from the interaction of diverse components; health comes from dynamic balance across differences, not from any single optimal state. This is where Plurality becomes a genuine worldview—not just about democracy or technology, but about what makes systems robust, adaptive, and flourishing.

Reader: That’s an ambitious vision. But when I look at the world, I see increasing polarization, fragmenting publics, democracy backsliding globally. If Plurality is such a good framework, why isn’t it winning?

Hilma: Because having good ideas isn’t enough—you need infrastructure, institutions, and incentives that embody those ideas. This is where Taiwan’s experience becomes crucial. They didn’t just theorize about Plurality; they built it into national digital infrastructure during a period when they had urgent need and political will.

Most democracies haven’t faced Taiwan’s particular pressures, living with the constant threat of an authoritarian neighbor that claims sovereignty over you. Taiwan can’t afford democracy to fail or polarization to spiral out of control—their survival requires finding ways to coordinate despite differences.

This created political space for experimentation that most established democracies lack. When everything’s mostly working, the incentive to fundamentally rethink democratic infrastructure is weak. Why fix what isn’t (obviously) broken? But Taiwan’s success is now providing templates that other jurisdictions are beginning to adopt—not necessarily because they’re in as tight a situation as Taiwan, but because they can see these tools working and want to import them before their own democratic challenges become crises.

Reader: Okay, I’m following the broad vision. But Plurality seems to cover an enormous amount of ground. What are the most important pieces for understanding how it actually works?

Hilma: For our purposes, I want to focus on the three interconnected aspects of Plural Identity, Augmented Deliberation, and Plural Voting. Each addresses a fundamental challenge in democratic coordination, and together they form a coherent approach to collective intelligence.

Let me start with Plural Identity because it’s foundational—you can’t have meaningful democratic participation without established identities, but identity systems create enormous power and privacy tensions.

Current digital identity is a mess. We’re caught between inadequate government IDs and invasive corporate surveillance. Government-issued IDs like passports or social security numbers are highly trusted but based on thin signals—essentially a birth certificate chain. They’re used across countless contexts despite being designed for specific purposes, creating security vulnerabilities. Your social security number was meant for pension administration; now it’s a universal identifier that anyone who knows it can weaponize.

Corporate single sign-on systems—“Sign in with Google/Facebook/Apple”—are far more sophisticated. They leverage rich behavioral data to verify identity and prevent fraud. But this richness comes at a cost: these companies gain comprehensive views of your online activity. They see everywhere you go, everything you do. The identity verification is strong, but the surveillance is total.

Reader: So we’re stuck between weak-but-trusted and strong-but-invasive?

Hilma: That’s the conventional framing, yes. Plural Identity offers a third way by recognizing that people aren’t just biological beings but fundamentally social beings. Your identity isn’t primarily your biometrics or your government documents—it’s the entire web of relationships, interactions, and affiliations that constitute your social existence.

Think about what you’d actually use to prove who you are to someone who knows you. Not your fingerprints or passport number, but shared experiences: “Remember when we went to that concert?” “I’m the person who worked with you on the tree planting project.” “I’m Laura’s friend from college.” Your identity is constituted by these relationships and shared histories.

Plural Identity builds on this social reality. Instead of relying on a single source of verification—whether government or corporation—it draws on the entire network of people and institutions who can vouch for various aspects of your identity. Want to prove you’re over eighteen? Your school might verify your graduation year. Friends who’ve known you for years can confirm. Doctors who’ve treated you have records. Multiple independent sources, none of which individually need comprehensive data about you.

Reader: But doesn’t that just shift the privacy problem? Now instead of one entity knowing everything, you have dozens of entities each knowing something about me?

Hilma: Here’s the crucial difference: these organizations know things about you from natural social interactions that we don’t typically experience as privacy violations. Your school knows when you graduated because you attended there. Your doctor knows your medical history because you received care. Your friends know your approximate age because they’ve known you for years. This information exists in social relationships that have their own contexts and norms.

The privacy violation happens when this information is aggregated, decontextualized, and used for purposes beyond the original relationship. Facebook knowing your medical history is creepy; your doctor knowing it is expected. Your employer knowing your religious practices might be inappropriate; your religious community knowing them is normal.

What Plural Identity systems aim to preserve is what scholar Helen Nissenbaum calls “contextual integrity”—ensuring information stays within appropriate social contexts rather than leaking across them inappropriately. The technology now exists, in the form of zero-knowledge proofs, to prove you’re old enough to drink without revealing your exact birthdate, or that you’re qualified for a job without sharing your complete educational history.

Reader: This sounds elegant in theory, but surely managing verification relationships with dozens of entities is incredibly complex?

Hilma: That’s the technical challenge, yes. But here’s where modern technology actually helps rather than hinders. You don’t need to individually manage these relationships—you need systems that can orchestrate them on your behalf. Think about how you prove your identity now. You might show a driver’s license to get into a bar, a passport for international travel, a work badge to enter your office. You’re already managing multiple identity credentials, each appropriate to different contexts.

Plural Identity systems may also leverage “transitive trust”—you trust your friend, your friend trusts someone else, and that chain can establish limited trust even with strangers. Research shows most humans are within six degrees of separation from each other. Plural Identity harnesses those chains, finding paths of verification through your social network rather than requiring direct relationship with every verifier. The Circles project is an attempt to build a whole new monetary system based on this idea.

Reader: What about recovery if you lose access? That’s a huge problem with blockchain-based identity systems—lose your keys and you’re permanently locked out.

Hilma: This is where Plural Identity’s social foundation really shines. Instead of relying on a single key or a single authority, you can establish “social recovery”—for example, three of five trusted friends or institutions can collectively recover your credentials. This is already becoming the gold standard in Web3 communities and is being adopted even by mainstream platforms like Apple.

The key insight: your identity is constituted by your relationships, so your relationships should be able to reconstitute your identity if something goes wrong.

Reader: Alright, Plural Identity makes sense as a foundation. But how does that connect to the deliberation tools like Pol.is you described earlier?

Hilma: Plural Identity establishes who can participate; Augmented Deliberation determines how they participate together.

The fundamental challenge is what we might call the diversity-bandwidth trade-off. When you try to include people with vastly different perspectives in conversation, discussions become lengthy, costly, difficult to resolve. But when you increase efficiency and bandwidth, you tend to exclude diverse perspectives—someone has to represent others, or conversations fragment into isolated groups that never interact.

Reader: So how does augmenting this with digital tools improve things?

Hilma: By radically expanding who can participate while maintaining or even improving deliberative quality. Traditional face-to-face deliberation might include twenty to two hundred people over a day—perhaps thousands if you use methods like World Café. But reaching millions while preserving deliberative richness seemed impossible.

Pol.is doesn’t replace face-to-face deliberation but complements it by making certain aspects scalable. The clustering shows participants where they stand in opinion space. The bridging mechanisms surface areas of potential consensus. These features together create something genuinely new: asynchronous mass deliberation that increases understanding rather than calcifying divisions.

What’s promising is how this is being integrated with other deliberation tools to create a kind of ‘deliberation ecology’. Cortico, a nonprofit developed in collaboration with MIT’s Center for Constructive Communication, focuses on amplifying underheard voices. Small groups record conversations on challenging topics, and through systematic listening—led by people, supported by AI—patterns and themes are surfaced across many conversations.

Large language models are opening genuinely new possibilities in this area—some exciting, some concerning. On the exciting side: they can help overcome what I’d call the “broad listening bottleneck.” Herbert Simon observed that “a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention.” Even with perfect information from thousands of participants, someone has to read and synthesize it—this typically limits deliberation scale. The Talk to the City project demonstrates one approach: instead of reading through hundreds of statements to understand a group’s perspective, you can explore AI-generated reports that identify themes and summarize claims while grounding every insight in verifiable participant quotes—dramatically reducing cognitive load while preserving nuance. Anthropic’s constitution for Claude was developed partly through Pol.is consultations that were then synthesized using language models.

Reader: I’m immediately suspicious of that. Aren’t we just outsourcing democratic deliberation to machines? That seems like exactly the wrong direction.

Hilma: Your suspicion is warranted. This is where the line between assistive and replacing becomes crucial. The concerning version is what Tang calls “Habermas Machine”—software that interviews people individually, builds digital twins of them, then lets those digital twins deliberate “in silico” while humans wait for results. As Tang says: “That’s like sending robots to the gym to lift weights for us. I’m sure they’re very impressive. But what’s the point?” We cannot delegate democracy itself. The civic muscles must be exercised by actual humans.

The healthy version keeps humans in the loop at every crucial point. LLMs help with synthesis and translation, but humans still make the actual decisions, review the syntheses for accuracy, engage with each other rather than only with machines. The technology makes the conversation more efficient and inclusive; it doesn’t conduct the conversation itself.

Reader: Couldn’t these systems be manipulated? And if they only work when people are already somewhat cooperative, how much are they actually accomplishing?

Hilma: Both valid concerns. The bridging algorithms in Pol.is and Community Notes are designed to resist simple gaming—you can’t just coordinate with others in your bubble to upvote your preferred statements, because the system specifically looks for support across clusters. But more sophisticated attacks are possible: astroturfing, adversarial statements that technically bridge clusters while advancing harmful agendas. The defenses are multiple: algorithmic detection combined with human oversight, identity systems that make mass fake account creation difficult, transparency about how algorithms work so communities can audit them.

As for the cooperation question: these tools work best where there’s some baseline of good faith. They’re not magic bullets for purely adversarial environments. But most political situations aren’t purely adversarial—they’re mixed-motive. People have genuine disagreements but also genuine shared interests. The problem is that conventional platforms amplify adversarial aspects while suppressing cooperative potential. These tools don’t create cooperation from nothing, but they can help latent cooperation become actual coordination. That’s valuable even if it’s not universal.

Reader: We’ve talked about identity and deliberation. What’s Plural Voting, and how does it fit into this picture?

Hilma: Voting is where deliberation becomes decision. After all the conversation and synthesis, eventually groups need to make definite choices: allocate resources, pass laws, set priorities. Voting provides a way to do this that’s relatively quick, inclusive, and legitimate—at least compared to alternatives like autocracy or endlessly seeking consensus.

But conventional voting—one person, one vote, majority wins—has severe limitations. It tends toward “lesser of two evils” dynamics where people vote strategically rather than honestly. It treats all preferences as equally intense, missing that people care much more about some issues than others. It often produces majoritarian tyranny, where slight majorities consistently override minority interests.

Plural Voting mechanisms attempt to address these problems by incorporating two crucial pieces of information that conventional voting ignores: the intensity of preferences and the independence of voters.

Reader: What do you mean by “independence of voters”?

Hilma: This is subtle but crucial. Suppose you’re trying to make a collective decision in a community, and you have two groups weighing in. Group A has ten thousand members who’ve all been exposed to the same information sources, belong to the same organizations, and vote identically. Group B has one hundred members who are genuinely diverse—different backgrounds, different information sources, different reasoning processes—but happen to agree on this particular issue.

In conventional one-person-one-vote, Group A crushes Group B simply through numbers. But there’s an argument that Group B’s agreement is actually more informative. When diverse, independent people converge on the same conclusion through different reasoning paths, that’s stronger evidence than many correlated people reaching the same conclusion through identical processes.

Reader: So you’re saying identical votes from highly correlated people should count less than diverse votes from independent people?

Hilma: That’s the core insight, though implementing it is complex. The principle is called “degressive proportionality”—voting weight that grows sublinearly with the number of voters when those voters are correlated.

This principle underlies Quadratic Voting, which Weyl helped develop. Instead of one vote per person, each person gets a budget of “voice credits” they can spend across multiple issues. Buying one vote on an issue costs one credit, but buying two votes costs four credits, three votes costs nine credits—the cost is quadratic. This lets people express preference intensity: care intensely about something, spend many credits to get multiple votes. Care mildly, spend few credits.

The quadratic cost creates an automatic trade-off that reveals true priorities. You can’t just max out votes on everything—you have to choose where to spend your limited budget. This aggregates not just direction of preferences but their strength.

Reader: I can see how that handles preference intensity. But where does the independence thing come in?

Hilma: Standard Quadratic Voting assumes voters are independent. When that’s violated—when voters are correlated or coordinating—the mechanism can be exploited. This is where Plural Voting can be extended beyond simple QV to incorporate social structure.

Vitalik Buterin came up with a pairwise approach. Instead of giving each individual a fixed budget, you give each pair of individuals a budget to split based on how similarly they vote. If you and I agree on everything, our pair’s budget contributes little to outcomes because we’re just duplicating the same signal. If we agree on nothing except one particular issue, our pair’s budget allocates heavily to that issue—revealing rare common ground.

This makes the determination of independence endogenous to the mechanism rather than requiring external assessment. The system automatically discounts coordinated voting and rewards genuine diversity of thought. A hundred people with genuinely independent perspectives get far more collective weight than a hundred people who all consume identical media and vote identically.

Reader: Has this actually been implemented anywhere, or is it just theoretical?

Hilma: It exists at various stages of deployment. Standard Quadratic Voting has been used in Taiwan’s Presidential Hackathon for project selection. The connection-oriented extensions are newer and more experimental—they’ve been used in some web3 funding contexts, like Gitcoin’s Cluster-Matching QF, but not yet at governmental scale.

What’s particularly exciting is that we’re now seeing experiments with augmented deliberation and plural voting combined, like RadicalxChange’s recent project with Colorado’s Office of Climate Preparedness and Disaster Recovery. They designed a three-step process: randomly-selected citizens first discussed their lived experiences with climate impacts in small facilitated groups; then they moved to a Pol.is consultation that mapped opinion clusters and surfaced areas of consensus; finally, they used Plural Voting to express not just which priorities they supported but how intensely. The whole process took just three and a half hours online, yet participants described feeling genuinely heard—some were quite emotional about the experience.

Reader: I’ve been trying to be open-minded, but these mostly sound like toy projects. I have serious questions about whether any of this is actually workable at scale.

Hilma: This brings us naturally to the critiques of Plurality. Let’s start with perhaps the deepest challenge: coordination and bootstrapping. Plural systems require participants to coordinate to use them rather than defaulting to simpler mechanisms or existing power structures. But coordination problems are precisely what make technological governance difficult in the first place!

Consider the transition problem: to benefit from Plural Identity, many organizations need to issue credentials and many services need to accept them. But why would any single organization invest in becoming an early issuer when few services accept the credentials yet? And why would services accept plural credentials when few users have them?

One possible solution is government leverage—mandating that certain public services accept and issue plural credentials, creating initial demand and supply simultaneously. But this requires state capacity and political will that many jurisdictions lack. It’s something of a catch-22: the places that can successfully mandate adoption are places that already have functional governance, while the places most in need of better democratic infrastructure lack the capacity to bootstrap it.

Reader: What about the technical complexity of these systems? I’m concerned about who actually understands and controls them.

Hilma: This gets at what I think is Plurality’s deepest tension: a system designed to democratize power might simply transfer it to a different elite.

The platform is political, as Langdon Winner taught us. Choices about which clustering algorithms to use, how to weight independence metrics—these are fundamentally political decisions dressed in technical language. If these decisions are made by small teams of engineers, we’ve just traded one form of elite control for another.

The problem goes beyond who designs the systems to whether anyone else can verify them. Conventional voting is transparent: you can understand one-person-one-vote and confirm that votes were counted correctly. When I cast a ballot, I grasp what happens to it. Plural Voting requires trusting far more complex mechanisms. When I submit a statement to Pol.is and the algorithm clusters me based on voting patterns, weights my input according to social graph independence metrics, and surfaces bridging statements using criteria I can’t fully grasp—I’m trusting a black box. Democratic legitimacy has traditionally rested partly on comprehensibility. Plurality’s sophistication undermines this.

The response from advocates is that these systems should themselves be governed plurally—open-source code, transparent algorithms, participatory design processes. There’s genuine effort here: vTaiwan and Pol.is are open-source, Tang made all her ministerial meeting transcripts public. But open-sourcing code doesn’t democratize power if most citizens can’t read code. Recent improvements in the ability of modern AI tools to translate code to natural language (and vice-versa) do hold some promise here.

Reader: There’s also a simpler concern I keep coming back to: even with perfect tools, meaningful deliberation takes time. How does this scale?

Hilma: This may be the most practically significant limitation. Pol.is consultations typically run for weeks. Face-to-face assemblies require hours or days of participant time. Deliberative quality—the thing that makes Plurality valuable rather than just another voting mechanism—is inherently slow. How many issues can a society deliberate on this way before participants burn out or tune out? As Tang herself acknowledges, democracy needs to be “fast, fair, and fun.” If it’s only fair but slow and tedious, participation collapses.

vTaiwan addressed this by being selective—focusing on genuinely contentious issues where deliberation adds clear value rather than trying to deliberate everything. Join provides lighter-weight participation for simpler matters. But this creates a new problem: who decides which issues merit deep deliberation?

That’s a gatekeeping function, and it reintroduces exactly the kind of power asymmetry Plurality aims to eliminate. Strategic actors might force attention-consuming consultations on topics where they want to slow progress. Or captured gatekeepers might route inconvenient issues to the shallow track. The scarcity of deliberative attention means someone must allocate it, and that allocation is itself a political act.

There’s a structural tension here: the deliberative depth that makes Plurality meaningful may be fundamentally incompatible with the scale it aspires to.

Reader: These critiques are substantial. But I note that Taiwan’s democratic metrics have actually improved even as democracy has declined globally. So clearly something is working, even if imperfectly. Where does Plurality go from here? How does it scale beyond interesting experiments to actual civilizational infrastructure?

Hilma: This is where we need to think about Plurality not just as clever tools but as a comprehensive policy vision—what Weyl and Tang call the building of a “Plural infrastructure” for democratic societies.

The ambition is staggering: within a decade, they envision the primary financial support for fundamental digital protocols shifting from private enterprise, to public funding from governments and charitable initiatives. The aim is for digital public infrastructure to receive roughly 1% of GDP globally—nearly a trillion dollars each year. This would increase public investment in digital infrastructure by multiple orders of magnitude.

Reader: That’s... ambitious. Where does the trillion dollars come from? Governments are already stretched thin.

Hilma: Weyl and Tang propose what they call “Directly Plural” taxes—revenue mechanisms that don’t just fund Plural infrastructure but actively enact Plural principles themselves. Progressive taxes on concentrated computational power—both raising revenue and discouraging excessive concentration of AI capabilities. Taxes on digital advertising that fund alternative, non-surveillance-based business models. Taxes on exclusive control of digital assets like spectrum or virtual spaces, with revenue supporting commons-based alternatives.

The precedent is the gas tax in the US. Initially opposed by the trucking industry, it was eventually embraced when funds were dedicated to building roads. The tax created a drain on the industry, but its indirect benefit—funding infrastructure the industry needed—more than compensated.

Reader: That seems politically implausible. Tech companies have massive lobbying power. Why would they accept this?

Hilma: The vision doesn’t rely primarily on convincing tech giants. It aims to build alternative infrastructure that’s so clearly beneficial that demand becomes politically irresistible.

The path is: first demonstrate that these tools work through local implementations like Taiwan, California, Japan, Finland. Build public understanding of digital democracy’s benefits. Create constituencies who’ve experienced better governance and demand it continues. Eventually, the question shifts from “should we do this?” to “how quickly can we scale this?”

We’re seeing early signs: the EU developing its own digital identity and payments infrastructure, the UN and G20 recognizing digital public infrastructure as a priority, multiple jurisdictions experimenting with participatory platforms.

Reader: Alright. I’m cautiously intrigued by Plurality while remaining skeptical about its scalability. Where does this fit in our larger metamodern story?

Hilma: Plurality’s metamodern character should be clear by now. It believes in democratic progress while being realistic about coordination challenges. It reconstructs democratic infrastructure rather than just critiquing its failures. It holds that both individual autonomy and collective coordination matter—we need robust identity protection and rich social verification, private deliberation and public synthesis, diverse preferences and collective choice.

Connecting our conversation to the previous chapter, I see d/acc and Plurality as highly complementary. d/acc focuses on what to build; Plurality suggests how to build it. d/acc gives us the substantive agenda—biosecurity, resilient infrastructure, cryptographic privacy, epistemic security. But it’s relatively thin on process: how do diverse populations actually decide which technologies count as “defensive”? Who determines what “decentralizing” means in contested cases? When values conflict, how do we navigate those trade-offs collectively? This is precisely where Plurality enters—providing the democratic infrastructure that d/acc’s vision requires.

It won’t have escaped you that most of what we’ve discussed so far lives primarily in the world of bits—digital identity, online deliberation, cryptographic infrastructure. But people need to eat. They need shelter, energy, manufactured goods. The question becomes: can we apply these same principles—defensive, decentralizing, democratically governed—to physical production itself? That’s where Cosmolocalism enters—asking how communities might produce what they need in ways that are globally connected yet locally rooted, drawing on shared knowledge while remaining grounded in place. Let us continue.

⿻ 數位 Plurality: The Future of Collaborative Technology and Democracy

Right Livelihood: Announcement of the 2025 Laureates: Audrey Tang

How Pro-Social Technology Is Saving Democracy from Big Tech with Audrey Tang | TGS 169

Meta-Politics: Designing Digital Environments for Civic Power with Audrey & Nathan Schneider