Cosmo-localism

Chapter 6, part 3 of Technological Metamodernism

Previously:

Reader: We’ve covered d/acc and Plurality—both fairly abstract frameworks about defensive technology and democratic coordination. I’m curious about approaches that feel more... material? Like, actual manufacturing and production rather than just digital infrastructure?

Hilma: Then let me tell you a story from March 2020, featured by The Alternative. A hospital in Brescia, northern Italy—one of the hardest-hit regions in the early COVID-19 pandemic. Patients were dying from respiratory failure. The hospital had ventilators, but they were running out of a small plastic valve called a Venturi valve, essential for the machines to function. Without these valves, which cost about three euros each, the ten-thousand-euro ventilators became useless metal boxes. People would die for want of a piece of plastic the size of your thumb.

The hospital contacted the valve’s supplier. The response was devastating: they couldn’t deliver new valves in time. The supply chain was broken. In normal times, manufacturing ran smoothly—orders placed, products shipped, inventory managed. But nothing about early 2020 was normal. Factories were shutting down. Borders were closing. Logistics networks were seizing up. The global just-in-time supply chain that seemed so efficient in peacetime revealed itself as catastrophically fragile in crisis.

The hospital was desperate. Nunzia Vallini, a local journalist, reached out to Massimo Temporelli, founder of a maker space in Milan. Could they 3D print the valves? Temporelli made calls to fab labs and companies in the region. Within hours, a small engineering company called Isinnova responded. The founder, Cristian Fracassi, brought a 3D printer directly to the hospital.

Reader: But surely you can’t just casually 3D print medical equipment? There must be regulations, certifications, safety testing...

Hilma: You’re right to be concerned—and there’s a fascinating tension here. The original manufacturer held the patent and initially refused to share the design files. The hospital couldn’t provide them either, citing intellectual property concerns. So Fracassi and his team measured the original valve by hand, reverse-engineered it, and redesigned it for 3D printing—all within a few hours.

Were they violating patent law? Probably. Was there time for safety testing? No. They made what they needed and installed it. Ten patients went from suffocating to breathing because of 3D-printed plastic that cost about a euro to produce and took a few hours to make.

The story went viral. Within days, makers around the world were sharing designs for face shields, mask adjusters, respirator parts—anything hospitals needed and couldn’t get from fractured supply chains. An entire ecosystem of distributed manufacturing sprang into existence almost overnight, coordinated through social media, GitHub repositories, and maker networks. Design files traveled at light speed across the internet. Physical objects materialized in workshops from Seattle to São Paulo.

This is cosmo-localism. Not as abstract principle but as lived reality. Design files—light as information—circulating globally through digital commons. Physical production—heavy as atoms—happening wherever it’s needed, using whatever resources are locally available. The global cooperating to serve the local. The local contributing back to the global.

As Kate Raworth tweeted at the time: “This is how the distributive, open-design economy will emerge—by demonstrating its agility and resilience in response to the breakdown of the centralised, closed-design economy.” The pandemic didn’t create cosmo-localism. But it revealed its potential with brutal clarity. When the globalized supply chain broke, distributed networks of makers kept people alive.

Reader: That’s a powerful story. But I’m guessing cosmo-localism has deeper roots than just a crisis response? What’s the intellectual history?

Hilma: The term “cosmopolitan localism” was pioneered by Wolfgang Sachs, a scholar at the intersection of environment, development and globalization, and a follower of Ivan Illich, who we first met in chapter 3.

Sachs was writing in the 1990s, but drew on much older currents. On one side, classical cosmopolitanism—the Stoic idea that we’re all citizens of a world community, not just our local city-state. On the other side, localization movements that emerged in the 1970s and 80s as critiques of globalization—emphasizing the importance of place, local knowledge, community self-sufficiency.

Reader: Those seem like awkward bedfellows. How do you combine them?

Hilma: Sachs proposed that we need to “amplify the richness of a place while keeping in mind the rights of a multifaceted world.” To be deeply rooted AND globally connected. Locally autonomous AND participating in planetary mutual aid.

The key insight is distinguishing between different kinds of things that can be global. Sachs was writing during the high neoliberal moment—when “globalization” meant corporate supply chains, financial flows, homogenizing consumer culture. Against this, he argued for a different kind of global connection—one based on knowledge sharing, cultural exchange, solidarity across difference. You could be open to the world without being colonized by it.

Reader: How did this connect to actual production and technology?

Hilma: The breakthrough came with the development of digital fabrication technologies in the 2000s and early 2010s, providing the technical means to turn globally shared digital designs into locally manufactured physical objects. By around 2015, researchers like Michel Bauwens, Jose Ramos and Vasilis Kostakis were developing comprehensive frameworks showing how this model could fundamentally transform production.

Different genealogies began interweaving under the banner of cosmo-localism. The sustainability crowd concerned about shipping emissions. The maker movement celebrating open-source hardware. Commons scholars documenting peer production. Post-development theorists critiquing neo-colonial globalization. Transition town organizers building local resilience. These disparate streams began recognizing they were articulating complementary visions.

Reader: That gives me a basic sense of of the history. Time to get a bit clearer on what cosmo-localism actually is as a framework.

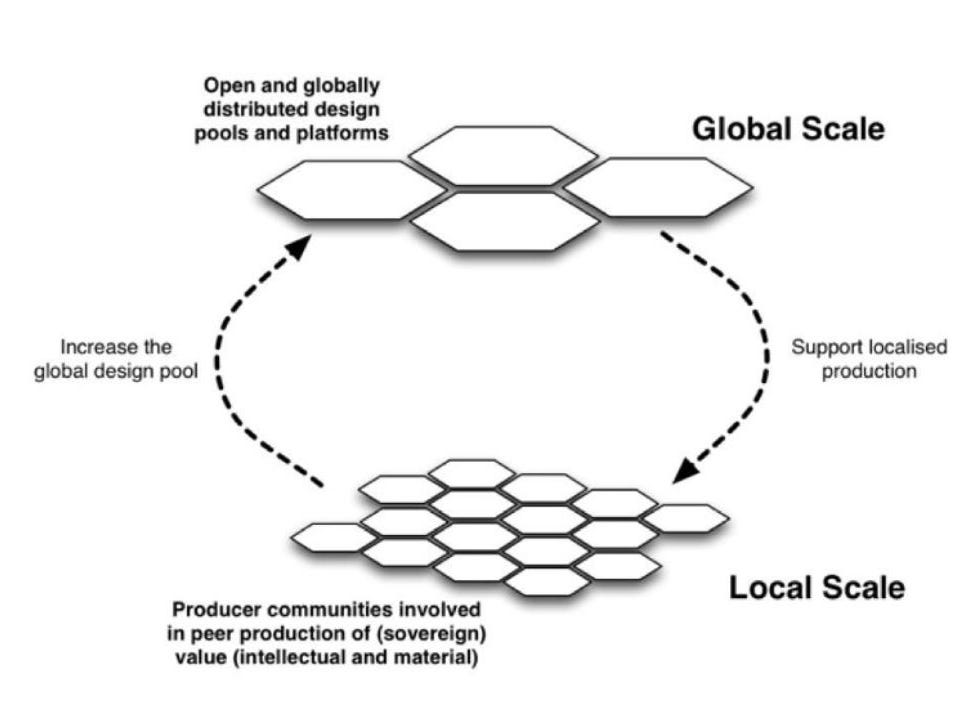

Hilma: At the most basic level, cosmo-localism describes the process of bringing together globally distributed knowledge commons with locally situated production capacity. The shorthand formula is “Design Global, Manufacture Local”—sometimes abbreviated as DGML.

“Design Global” means knowledge, innovation, and creative solutions are developed collaboratively and shared freely across a planetary network. It’s what Jose Ramos calls the “IIDEAS commons”: Ideas, Innovations, Designs, Experiments, Actions, Solutions. It’s the accumulated technical and social knowledge of humanity, made accessible to everyone.

Wikipedia demonstrated that you could create a comprehensive knowledge resource through voluntary contribution, with quality emerging from collective verification rather than centralized editorial control. The IIDEAS commons applies similar logic to production knowledge.

This brings us to “Manufacture Local”—the other half of DGML. Physical production happens as close to need as practical, using local resources, local labor, local manufacturing capacity. Not because localism is ideologically superior but because physics and thermodynamics make it preferable. Shipping atoms is expensive, energy-intensive, fragile. Shipping bits is cheap, low-energy, robust.

The early articulations of DGML focused heavily on digital fabrication and manufacturing because that’s where the technical possibilities were most obvious. But the underlying logic applies much more broadly.

Consider food production. Permaculture principles, agroecological techniques, seed varieties, pest management strategies—these can all be part of a global commons while actual cultivation happens locally, adapted to local ecology, climate, soil, culture.

Or energy. Communities can learn from each other about solar installation, wind turbine design, micro-hydro systems, grid management—while actual energy production and consumption happens within bioregional boundaries, matched to local renewable resources.

The same pattern extends to healthcare, education, governance, culture. The fundamental dynamic is: share knowledge and coordinate learning globally while embedding practice in particular places with particular people addressing particular needs. This prevents both the tyranny of imposed universal solutions and the poverty of isolated local struggles.

Reader: But surely some things have to be made at scale in specialized facilities? You can’t manufacture computer chips in your garage.

Hilma: Absolutely. Cosmo-localism isn’t naive about this. The framework recognizes different levels of production complexity and different appropriate scales for different products. Some things—microprocessors, advanced medical equipment, precision instruments—genuinely require specialized centralized manufacturing. The cosmo-local response isn’t to reject this reality but to ask: what can we relocalize without sacrificing quality or capability? And how do we organize the necessary global production to serve distributed local needs rather than extractive accumulation?

Bauwens and Ramos write that cosmo-localism operates on the subsidiarity principle—decisions and production should happen at the most local level practical, with higher scales invoked only when genuinely necessary. A neighborhood can produce furniture, preserve food, generate some energy locally. A city or bioregion can manufacture more complex goods, operate larger fabrication facilities, coordinate infrastructure. Some products genuinely require national or global manufacturing—but far fewer than current systems assume.

Current globalized production isn’t actually optimized for efficiency in any absolute sense. It’s optimized for capital accumulation within existing power relations. We manufacture clothing in Bangladesh not because that’s thermodynamically optimal but because labor is cheap and environmental regulations are weak. We ship components back and forth across oceans multiple times not because transportation is free but because each location offers some advantage for capital and capitalists—lower wages, tax breaks, lax oversight.

Reader: You’ve mentioned “bioregions” a couple of times. What’s that about?

Hilma: A bioregion is an area defined by natural rather than political boundaries—typically watersheds, mountain ranges, ecosystems. The concept emerged in the 1970s through thinkers like Peter Berg and Raymond Dasmann, who were trying to reimagine human settlement patterns aligned with ecological realities rather than arbitrary political divisions.

The key insight is that human communities are fundamentally embedded in living systems. The health of your community depends on the health of your watershed, your soil, your local ecology. Political borders are imaginary lines; watershed boundaries are material realities. When you live in a watershed, what you do upstream affects people downstream. When you share an airshed, pollution becomes everyone’s problem. When a forest stabilizes your hillsides and regulates your rainfall, everyone has a stake in its health.

Bioregionalism argues that aligning human organization with these natural systems creates more coherent governance, more sustainable resource use, more meaningful place-based identity. Instead of managing resources through nation-states whose borders bear no relation to ecological realities, you organize around the actual living systems on which communities depend.

Reader: So bioregional cosmo-localism means producing locally according to ecological boundaries rather than political ones?

Hilma: Precisely—and this combination creates something powerful. Cosmo-localism without bioregionalism can become just distributed manufacturing that still ignores ecological limits, still treats nature as raw material rather than living context. Bioregionalism without the cosmo-local framework lacks access to global knowledge commons, remains isolated in its innovations, can’t benefit from the collective learning of planetary networks.

Together, they form what Michel Bauwens calls a “cosmo-local plan for our next civilization.” The vision is regenerative communities rooted in bioregions, producing what they need using their bioregion’s resources sustainably, but connected to global networks of knowledge sharing, mutual aid, and coordinated learning. Local in production and governance, global in knowledge and solidarity.

This means each productive community has two interfaces, as Bauwens describes it. One interface is with bioregional neighbors—other communities in your watershed, your ecosystem, your geographical region. You coordinate on shared resources, manage commons together, ensure your collective impact stays within ecological boundaries. The other interface is with trans-local partners in similar domains—permaculture networks, renewable energy cooperatives, open hardware communities. You share knowledge, pool research and development, coordinate on technical standards.

Reader: The framework makes sense in theory. But is anyone actually trying to implement this at a meaningful scale?

Hilma: Yes—and the most ambitious attempt is the Fab City Global Initiative. But before I explain the initiative itself, I need to tell you about Fab Labs, because that’s where this story begins.

Fab Labs started almost accidentally as an outreach program from MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms in 2002. The idea was deceptively simple: provide public access to digital fabrication tools—3D printers, laser cutters, CNC mills, electronics equipment—plus training in how to use them. See what people create when they have access to manufacturing capacity usually locked behind factory gates or expensive makerspaces.

Reader: And what did people create?

Hilma: Everything. Solar-powered turbines for villages without grid electricity. Customized prosthetics for people with disabilities. Agricultural sensors for precision farming. Rapid prototypes of business ideas. Tools for traditional crafts enhanced with digital possibilities. Solutions to hyperlocal problems that no commercial market would address because the need was too specific or the market too small.

What emerged in these spaces wasn’t just Do-It-Yourself but what makers began calling “Do-It-Together” (DIT)—production as a fundamentally collaborative act. The shift from DIY to DIT matters: it signals that the point isn’t individual self-sufficiency but collective capability. A single maker with a 3D printer is a hobbyist. A community of makers sharing tools, skills, and designs is the seed of an alternative production system.

Naturally, every Fab Lab shared their designs, their processes, their learnings through the network. A fab lab in Vigyan Ashram, rural India, develops an LED lighting solution for areas without reliable electricity. They document it, share the design files. Fab labs in Kenya, Peru, rural China can manufacture and deploy the same solution, adapted to their contexts. Someone improves the design—better battery management, more efficient optics, easier assembly. That improvement flows back through the network to everyone.

By 2010, there were dozens of fab labs worldwide. By 2016, hundreds. Today, there are over two thousand, in more than 120 countries—an exponential growth curve doubling roughly every 24 months. They’ve created a global distributed manufacturing network, coordinated through shared infrastructure (the Fab Cloud where designs live), shared education (the Fab Academy training program), and shared principles (the Fab Charter establishing the network’s ethos and rules).

The network has also begun addressing a deeper bootstrapping problem: fab labs themselves depend on specialized equipment—CNC mills, laser cutters, precision electronics—that has to be manufactured somewhere. If that somewhere is a factory in Shenzhen, you’ve just recreated the dependency you were trying to escape. The response is the Super Fab Lab—a fab lab equipped with the machinery needed to build more fab labs. The first Super Fab Labs were established in Kerala and Bhutan, deliberately located for global inclusivity rather than in wealthy Western cities. The ambition is for regional Super Fab Labs to produce the labs needed for their regions, creating a self-reproducing infrastructure where the means of production can themselves be locally produced. It’s a small step, but the principle it demonstrates is significant: if you can manufacture your factories locally, not just your products, you’ve achieved a qualitatively different kind of resilience.

Reader: That’s impressive growth. But fab labs are still basically fancy workshops, right? How did this become about transforming entire cities?

Hilma: Fab labs, while powerful as local innovation hubs, faced a scaling problem. They were excellent at prototyping, at education, at demonstrating possibilities. But they typically couldn’t manufacture at sufficient volume to make a significant dent in urban provisioning systems. A fab lab might produce a few dozen solar lamps or several prosthetic hands. It couldn’t produce the thousands or millions needed to serve an entire city or region.

What if, instead of just having fab labs as isolated innovation spaces, you connected them into a comprehensive urban production ecosystem? What if cities deliberately built capacity to manufacture significant portions of what they consume locally—not just interesting prototypes but actual provisioning systems for food, energy, products?

This is the vision Tomas Diez and colleagues articulated when they launched Fab City in 2011. The goal: for cities to produce (almost) everything they consume by 2054, while sharing knowledge globally.

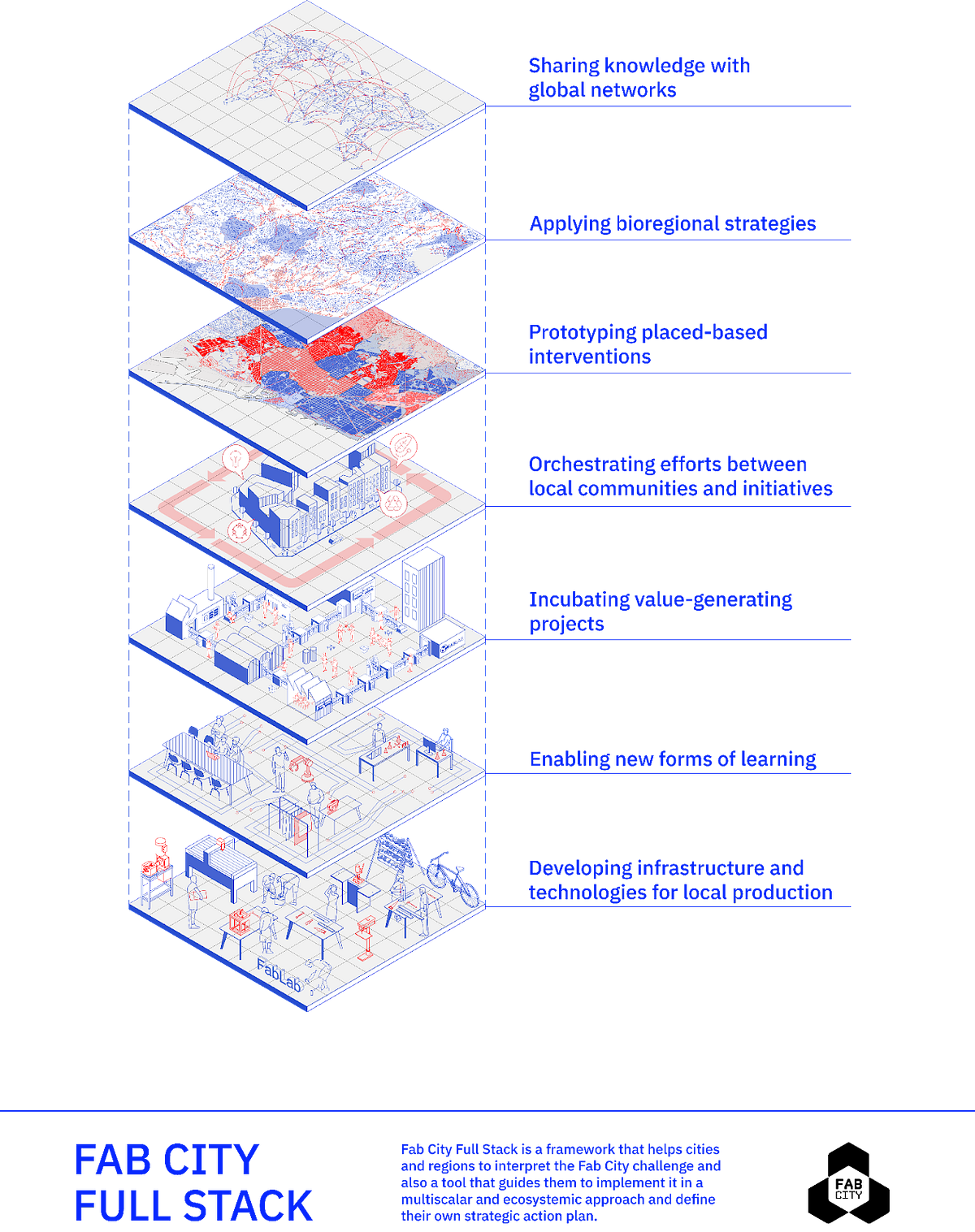

What makes the Fab City more than utopian manifesto is the framework they’ve developed for actually implementing it: the Fab City Full Stack. The stack includes seven distinct but interconnected layers—from foundational infrastructure (fab labs, maker spaces, the machines and communities within them) through education, project incubation, local coordination, place-based prototyping, and bioregional strategy, up to global knowledge sharing. The layers aren’t hierarchical or sequential—cities can start from wherever their existing strengths lie and build outward.

Infrastructure without education produces empty workshops. Education without coordination produces isolated makers. Coordination without policy engagement hits regulatory walls. The Full Stack is an attempt to address all of these dimensions together.

Consider what this looks like concretely. In 2016, Barcelona’s city council designated the Poblenou neighborhood—a 1.5 square kilometer former industrial district—as the city’s official “maker district,” essentially a living Fab City prototype. Working with Fab Lab Barcelona and in partnership with IKEA, organizers mapped existing businesses and institutions that aligned with the Fab City vision: fab labs, makerspaces, restaurants serving locally grown produce, small manufacturers. The vision was to connect these into a coherent productive ecosystem—not a single fab lab but a neighborhood where local production is embedded in everyday life. Residents experimented across three domains simultaneously: material production in makerspaces, food production on rooftops, and energy production via solar panels with domestic battery storage. IKEA explored what Tomas Diez described as a shift from warehouses outside the city where products travel thousands of kilometers, to neighborhood micro-factories manufacturing furniture on demand, potentially incorporating citizens’ own designs.

The results were mixed—political transitions complicated continuity, scaling beyond enthusiast communities proved difficult, and the ecosystem remained far more prototype than provisioning system. But Poblenou began to demonstrate what it actually feels like when a neighborhood starts treating production as something that happens here, not somewhere else.

Reader: Poblenou is one neighborhood in one city. How representative is it?

Hilma: Forty cities have joined the network including Amsterdam, Paris, Detroit, Seoul, São Paulo, Hamburg, Shenzhen, the entire kingdom of Bhutan and the region of Kerala. Each enters at different layers depending on existing capacities. Amsterdam focuses on circular materials and urban mining. Detroit on rebuilding manufacturing capacity after deindustrialization. Kerala on integrating traditional knowledge with digital tools.

Honestly, none are yet close to self-sufficiency. And unsurprisingly, where Fab Cities struggle most is complex manufactured goods—electronics, vehicles, machinery. These require supply chains, specialized components and economies of scale that localization can’t easily match. What is within reach, however, is regional production of some components, local assembly and customization, and circular systems for repair and remanufacturing rather than disposal and replacement.

Reader: How does the circular economy connect to cosmo-localism exactly?

Hilma: They’re almost necessarily linked. Traditional circular economy thinking—designing out waste, keeping materials in use, regenerating natural systems—runs into a fundamental problem at global scale: you can’t create closed loops if products are manufactured on one continent and consumed on another. Shipping used materials back to distant factories for reprocessing negates the environmental benefits and adds enormous complexity.

A circular economy needs local production capacity to actually work. Bioregional cosmo-localism provides it. Products manufactured locally can be designed for disassembly, with components and materials cycling back through the regional production ecosystem. Your old furniture becomes raw material for new furniture, made in the same city. Organic waste becomes compost for urban agriculture. Metals get refined and reused locally. Once you’ve established enough material circulating within the system, you need minimal new inputs—some replacement for degradation, energy and labor to keep things running, but the fundamental dynamic shifts from extraction and disposal to circulation and regeneration.

Reader: I’ll be honest—I’m both intrigued and skeptical. This vision is compelling, but it also feels somewhat... removed from how capitalism actually works? Like, global supply chains exist for reasons, right? They’re not just mistakes we can replace with local workshops.

Hilma: Now we’re getting to the juice. Let’s turn to the critiques, starting with the people who are sympathetic to cosmo-local ideals but deeply skeptical about whether the framework adequately grapples with economic reality.

The argument is that cosmo-localists are engaged in what we defined as “Game Denial”—the refusal to acknowledge how power and markets actually operate, expecting reality to conform to ideals through moral force rather than strategic engagement with existing constraints.

Let me articulate the steelman version of this critique: Global supply chains aren’t arbitrary or simply the result of corporate greed. They emerged because they solved real problems and created genuine value—even if they also created massive externalities. Specialized manufacturing achieves economies of scale that distributed production can’t match. Complex products require component integration across numerous suppliers. Quality control is easier with centralized production than coordinating thousands of small workshops. Capital investment flows to proven models with predictable returns, not experimental cooperatives with shared ownership and open IP.

The Game Denial accusation is that cosmo-localists treat these barriers as mere implementation challenges rather than structural features of capitalism that can’t be overcome without transforming capitalism itself—which is vastly harder than launching some fab labs and sharing design files.

Consider the open-source investment dilemma that Jose Ramos articulates as two contradictions:

Contradiction one: Make your IIDEAS free and open, and lose your ability to get investment capital. Investors want return on investment, and making designs open-source means giving away the monopoly that would generate returns. You’re creating value that capital can’t capture, so capital won’t fund you.

Contradiction two: Make your IIDEAS free and open, and support capitalism as usual. When you publish open designs, corporations with vastly more resources can appropriate them, patent incremental improvements, manufacture at scale you can’t match, and outcompete you using your own knowledge. You’ve just made corporate capitalism more efficient while undermining your own viability.

Reader: So what’s the cosmo-local response to these economic critiques?

Hilma: On the first contradiction, regarding capital: alternative funding mechanisms are emerging. Andrew Ward argues that community wealth building models can provide aligned capital without requiring unicorn-hunting venture capital. The investment thesis for local production is actually superior for certain investors—not because it offers spectacular returns but because it offers stable returns, builds real assets in places investors care about, creates community benefit they’ll directly experience.

On the second contradiction, regarding appropriation: the P2P Foundation has been grappling with this problem for years. One idea has been a reciprocation license—a peer production license that functions as intellectual property jujitsu. If a commercial entity wants to use a design, they pay the commons a commercial price. If another commons-based enterprise wants to use the design, it can be done at lower cost or freely. This creates a semi-permeable membrane—allowing value to flow from capitalism into the commons while preventing pure extraction in the opposite direction. Some ventures are exploring Fair Source licenses as another approach—making code publicly readable and modifiable but with initial restrictions to protect the business model, then converting to full open source after a delay.

It’s also worth noting that any competitive disadvantage isn’t inherent but contingent on policy. If you account for true costs—including carbon emissions, labor exploitation, environmental damage—localized production often becomes economically superior. The problem is that current systems externalize these costs, making destructive global production appear cheaper than it actually is. Change the policy environment—carbon pricing, fair labor standards, honest accounting—and local production becomes competitive.

There’s a genuine bind, similar to the challenges we saw with d/acc and Plurality: cosmo-localism needs different economic rules to thrive at scale, but building power to change those rules requires being viable under current rules.

Reader: Alright, so the economic pragmatists have their concerns. What about people coming from the other direction—the localists and bioregionalists? What do they make of all this?

Hilma: It’s instructive to consider the critique from Helena Norberg-Hodge and her colleagues at Local Futures, who have been advocating for economic localization for four decades. Their concern is that cosmo-localism, despite its name, doesn’t take the “local” seriously enough—that it smuggles back in problematic forms of globalization under the guise of knowledge sharing.

First, they argue that cosmo-localists overstate the internet’s role in enabling knowledge commons while ignoring its downsides. They point out—correctly—that knowledge sharing existed long before the internet. Local Futures’ own work in Ladakh in the 1980s involved introducing appropriate technologies like village-scale micro-hydro systems. Knowledge flowed globally through personal exchange, printed materials, workshops, people traveling to learn and teach. The internet makes sharing faster and cheaper but doesn’t create a fundamentally new possibility.

Worse, the internet carries enormous costs that cosmo-localists tend to minimize—energy consumption now a significant fraction of global electricity use, rare earth mineral extraction causing terrible environmental and social devastation, psychological harms from screen culture, the internet functioning as vector for Western consumerist cultural imperialism. Norberg-Hodge writes: “Despite the potential for the internet (de-corporatized and open-source) to play an important role in connecting our movements and sharing knowledge across the world, its shortcomings and costs must be kept constantly in mind, and it should not be construed as the sine qua non of knowledge commons, or conceived as an adequate substitute for face-to-face sharing and learning.”

The deeper critique is about techno-solutionism—the tendency to see new technologies as the answer rather than questioning whether more technology is needed at all. Norberg-Hodge argues that cosmo-localism, particularly its digital fabrication emphasis, doesn’t constitute sufficiently radical break from industrial alienation.

Consider the example of housing. Cosmo-localists celebrate projects like WikiHouse—open-source designs for houses that can be fabricated using CNC machines and assembled by non-experts. This eliminates dependence on construction monopolies, reduces costs, enables customization. What’s not to like?

But Norberg-Hodge asks: why are we manufacturing houses with machines when traditional building methods—adobe, cob, timber framing—could employ many more people, use local natural materials, require far less energy, and create skills that persist in communities? A traditionally-built earthen house achieves the same end—comfortable, environmentally sustainable dwelling—while employing human capacities and ecological knowledge that machine production eliminates.

Reader: So the critique is that cosmo-localism is still too enamored with high-tech solutions when low-tech alternatives might be superior?

Hilma: Correct, and it echoes the Schumacher-Bookchin divide: Schumacher treating ownership as a given and therefore distrusting high technology, Bookchin assuming ownership could change and thus considering automation as liberatory. Cosmo-localism inherits both sides of this unresolved conundrum, which is only intensifying in the age of AI.

But the concern extends from production to alienation itself. Even if manufacturing is local and uses open-source designs, if it’s done primarily by machines with humans as operators rather than craftspeople, Norberg-Hodge would claim you’ve lost something essential—the embodied knowledge, the hand-eye-heart-head coordination, the meaningful labor that connects people to materials and to each other.

She worries that cosmo-localism, despite its localist rhetoric, remains trapped in modernist assumptions: that urban concentration is inevitable, that efficiency should be prioritized over other values.

Reader: That’s a serious criticism. How do cosmo-localists respond?

Hilma: The response varies. Some acknowledge the critique’s validity while arguing for both-and: we need both high-tech distributed manufacturing AND revival of traditional craft, both digital knowledge commons AND face-to-face skill transmission, both 3D printing AND hand tools. The framework shouldn’t preclude low-tech solutions—it should enable communities to choose appropriate technologies for their contexts.

Others push back on what they see as fetishizing pre-industrial production. Sure, hand-building with local materials is beautiful and meaningful—but it’s also labor-intensive, requires skills most people no longer possess, produces at scales insufficient for eight billion humans. Digital fabrication might be alienating compared to traditional craft, but it’s liberating compared to dependence on global corporations for every object. Better to have local workshops with CNC machines than distant factories you have no access to or control over.

Reader: We’ve covered a lot of ground—the framework, the examples, the critiques. But I keep coming back to a basic question: how does this actually scale? Fab Cities have been at it for over a decade and even Barcelona isn’t close to self-sufficiency. Again, this seems like a series of toy projects rather than a serious plan for civilizational transformation.

Hilma: You’re right to press on this. There’s a profound gap between cosmo-local vision and current reality. Most initiatives remain what Michel Bauwens calls “pop-up political economies”—protected spaces where alternative rules apply temporarily, demonstration zones showing what’s possible, but struggling to expand beyond enthusiast communities.

The scaling question isn’t primarily technical. We know how to 3D print, how to share designs globally, how to organize knowledge commons. What we lack is the political and economic power to make cosmo-local production genuinely competitive with extractive globalization. This requires, among other things, what we might call narrative scaffolding—changing how people understand production, consumption, and economic possibility—and is the focus of The Alternative, initiated by Indra Adnan and Pat Kane.

The Alternative isn’t building fab labs or manufacturing networks directly. Instead, they’re constructing what they call a “Parallel Polis”—a term Václav Havel and Vaclav Benda used to describe how Czech dissidents imagined and prefigured alternative societies while living under Soviet domination.

The Alternative curates and connects emerging practices—cosmo-local production, plural governance, regenerative economics—into a coherent counter-narrative. They’re helping people see scattered experiments as part of a larger pattern, provisional seeds of a different civilization.

This matters because civilizational transitions require both material infrastructure and shared imagination. People need to envision alternatives before they’ll invest energy building them. The Alternative, along with authors like Paddy Le Flufy (Building Tomorrow) and Benjamin Life (regenerative accelerationism, ‘re/acc’), are providing that imaginative scaffolding, showing how cosmo-localism connects to bioregionalism, how both relate to new forms of governance, how all of this might constitute not just isolated improvements but a genuinely different way of organizing human provisioning.

Reader: But isn’t that just... storytelling? How does narrative translate into actual material change?

Hilma: Stories shape what people perceive as possible and legitimate. Right now, most people assume that complex goods must be made in factories halfway around the world, that local production can’t be sophisticated, that global supply chains are inevitable. These assumptions aren’t natural facts—they’re historically specific beliefs that serve particular interests. Change the story, and you change what actions seem reasonable.

Reader: We’ve covered a lot ground in this chapter—from ventilator valves to bioregionalism to fab cities to competing critiques. What’s the essential insight of cosmo-localism, and why does it matter for technological metamodernism?

Hilma: The techno-optimists say technology will save us through innovation and scale. The techno-skeptics say technology threatens us through alienation and extraction. Both are stuck in a frame where technology happens to localities from elsewhere—from Silicon Valley, from Chinese factories, from global supply chains. Cosmo-localism says: what if technology happened with bioregions, through bioregions, for bioregions—while remaining connected to global knowledge and solidarity?

The metamodern character appears in how cosmo-localism holds tensions. It’s radically local AND globally connected. It builds economic alternatives AND engages strategically with existing markets. It’s utopian in vision yet pragmatic in implementation—starting with what’s possible now while maintaining orientation toward transformation.

That the three frameworks of d/acc, Plurality and cosmo-localism—emerging from largely independent intellectual lineages—have arrived at such similar structural intuitions is worth pausing over. All are asking the same underlying question: how do you build systems that are robust without being rigid, open without being naive, coordinated without being controlled? d/acc asks this of infrastructure and defense. Plurality asks it of governance and communication. Cosmo-localism asks it of production and provisioning. Yet each reaches for the same repertoire of answers—subsidiarity, commons, distributed agency, the nesting of local autonomy within global cooperation. That convergence suggests something beneath the specific proposals: shared principles, a common grammar of technological metamodernism that none of these frameworks has fully articulated on its own. In the next chapter, we’ll try to make that grammar explicit.

The Pulsation of the Commons: The Temporal Context of Cosmolocal Transition

Fab Cities and the Urban Transformations of the 21st Century

Cosmo-localization & Localization: Towards a Critical Convergence

The three civilizational priorities of the next societal transition

Cosmo-local identities: We need a scalable, networked form of social cohesion

Moving Towards a Fourth Generation Civilization with Michel Bauwens

Cosmo-Local Commoning with Web3 - Michel Bauwens (P2P Foundation)

What is ‘cosmo-localism’? Why do we think it’s a game changer? And help fill out a dictionary for it

Beautiful Trouble - crafting a political Alternative - with Indra Adnan and Pat Kane

Fantastic, as usual Stephen!

I do hope you will be weaving the contemporary work of Yuk Hui - particularly his idea of cosmotechnism - into the narrative at some point.